Part One - Concept

Whether it be your own prose, a poem, or an article, the text you choose to illustrate will (obviously!) have a huge impact on the illustration you create. But remember,

illustration should seek to elevate a story. To be truly impactful, an image needs a strong concept, an original point of view that will serve the text without being redundant.

So it's important to go beyond the obvious, and find meaning between the words. How do we do that, you ask? Well, keep reading!

Step 1: Choose a text to illustrate

In this series, I will be illustrating an excerpt of The Garden of Living Flowers, chapter two of Lewis Carroll's "Through the Looking Glass." Feel free to follow along, or pick your own favourite piece — you can apply these steps to any text!

The Garden of Living Flowers

"I should see the garden far better,’ said Alice to herself, ‘if I could get to the top of that hill: and here’s a path that leads straight to it—at least, no, it doesn’t do that—’ (after going a few yards along the path, and turning several sharp corners), ‘but I suppose it will at last. But how curiously it twists! It’s more like a corkscrew than a path! Well, this turn goes to the hill, I suppose—no, it doesn’t! This goes straight back to the house! Well then, I’ll try it the other way.’

And so she did: wandering up and down, and trying turn after turn, but always coming back to the house, do what she would. Indeed, once, when she turned a corner rather more quickly than usual, she ran against it before she could stop herself.

‘It’s no use talking about it,’ Alice said, looking up at the house and pretending it was arguing with her. ‘I’m not going in again yet. I know I should have to get through the Looking-glass again—back into the old room—and there’d be an end of all my adventures!’

So, resolutely turning her back upon the house, she set out once more down the path, determined to keep straight on till she got to the hill. For a few minutes all went on well, and she was just saying, ‘I really shall do it this time—’ when the path gave a sudden twist and shook itself (as she described it afterwards), and the next moment she found herself actually walking in at the door.

‘Oh, it’s too bad!’ she cried. ‘I never saw such a house for getting in the way! Never!’

However, there was the hill full in sight, so there was nothing to be done but start again. This time she came upon a large flower-bed, with a border of daisies, and a willow-tree growing in the middle.

‘O Tiger-lily,’ said Alice, addressing herself to one that was waving gracefully about in the wind, ‘I wish you could talk!’

‘We can talk,’ said the Tiger-lily: ‘when there’s anybody worth talking to.’

Alice was so astonished that she could not speak for a minute: it quite seemed to take her breath away. At length, as the Tiger-lily only went on waving about, she spoke again, in a timid voice—almost in a whisper. ‘And can all the flowers talk?’

‘As well as you can,’ said the Tiger-lily. ‘And a great deal louder.’

‘It isn’t manners for us to begin, you know,’ said the Rose, ‘and I really was wondering when you’d speak! Said I to myself, “Her face has got some sense in it, though it’s not a clever one!” Still, you’re the right colour, and that goes a long way.’

‘I don’t care about the colour,’ the Tiger-lily remarked. ‘If only her petals curled up a little more, she’d be all right.’

Alice didn’t like being criticised, so she began asking questions."

Step 2: Gather your ideas

Reading through the text, three elements immediately stood out to me:

1/ There is an overall sense of other-worldliness throughout (the paths have a will of their own and twist like corkscrews, the flowers can talk, etc).

2/ The Looking-Glass world is confusing, and Alice can’t seem to understand its rules (she fails to simply go from A to B, time and space seem to collide, etc).

3/ The flowers are quite insulting and disdainful (Alice’s petals don’t curl up right, she looks stupid, etc).

Now, what stands out to you? List three elements that caught your attention, in the excerpt above or in your own text of choice. Without thinking about images yet, jot down a sentence that summaries your impressions, highlighting the strongest ideas. For example:

The scene is set in a bewildering garden, with fantastical undertones throughout, and features an unpleasant interaction between Alice and the flowers.

Once you have jotted down a sentence or two, think about how your ideas could elevate the text. One of the best way to do this is to think about your own personal point of view. After all, the way you interpret the text is unique to you, and will likely bring a fresh perspective to the story you have chosen to illustrate. In the example above, I could choose to focus on Alice being newly landed in a fantastical world where she clearly doesn’t belong (she doesn’t know the rules, doesn’t look right,etc). While the text describes her adventures so far in a series of sequential events, an illustration could collapse time and space to show everything at once, overwhelming the reader as much as Alice, and highlighting the truly bewildering nature of the garden of living flowers.

Meanwhile, you might choose to focus on Alice as a plucky and determined character, or on the Escher-like quality of the gardens, or, maybe, on how the flowers compare Alice to themselves: what is your point of you?

Step 3: Identify your concept

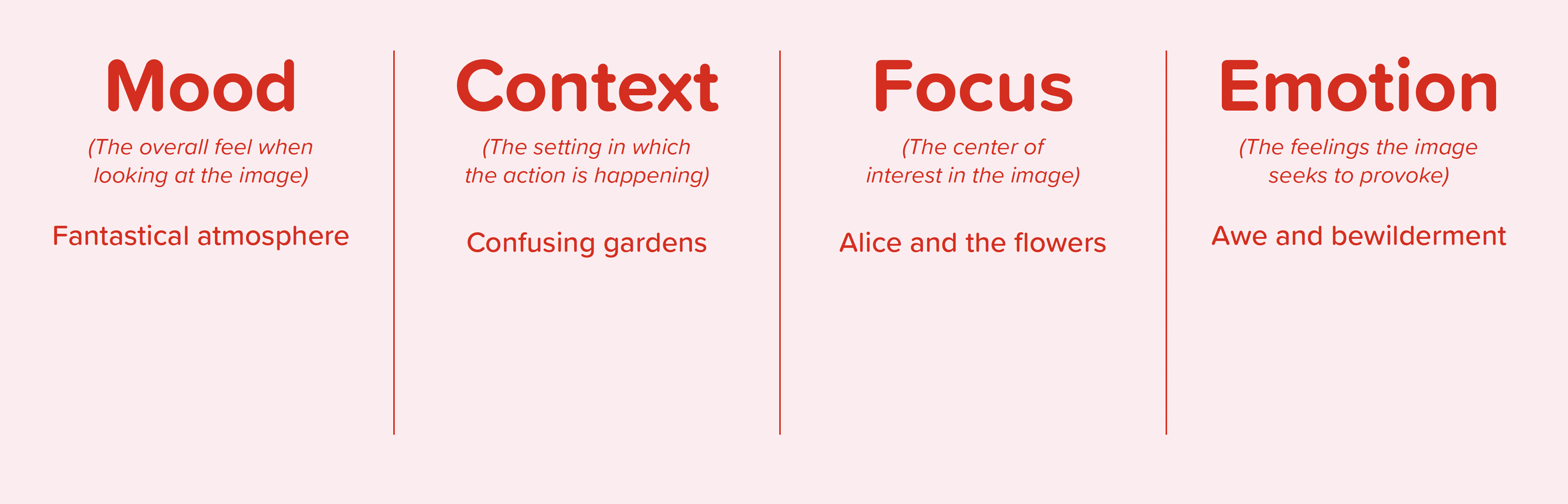

Next, I can start to translate these abstract ideas into a visual concept, using the framework below to fine-tune my point of view:

In my previous example, the dream-like, fantastical atmosphere would set the mood, the confusing garden and its nonsensical twists and turns would provides context for the scene, and the interaction between Alice and the flower would be the focus of the illustration. The overall emotion would be an overwhelming mix of awe and bewilderment, like a traveler might experience upon arriving in a truly unfamiliar place.

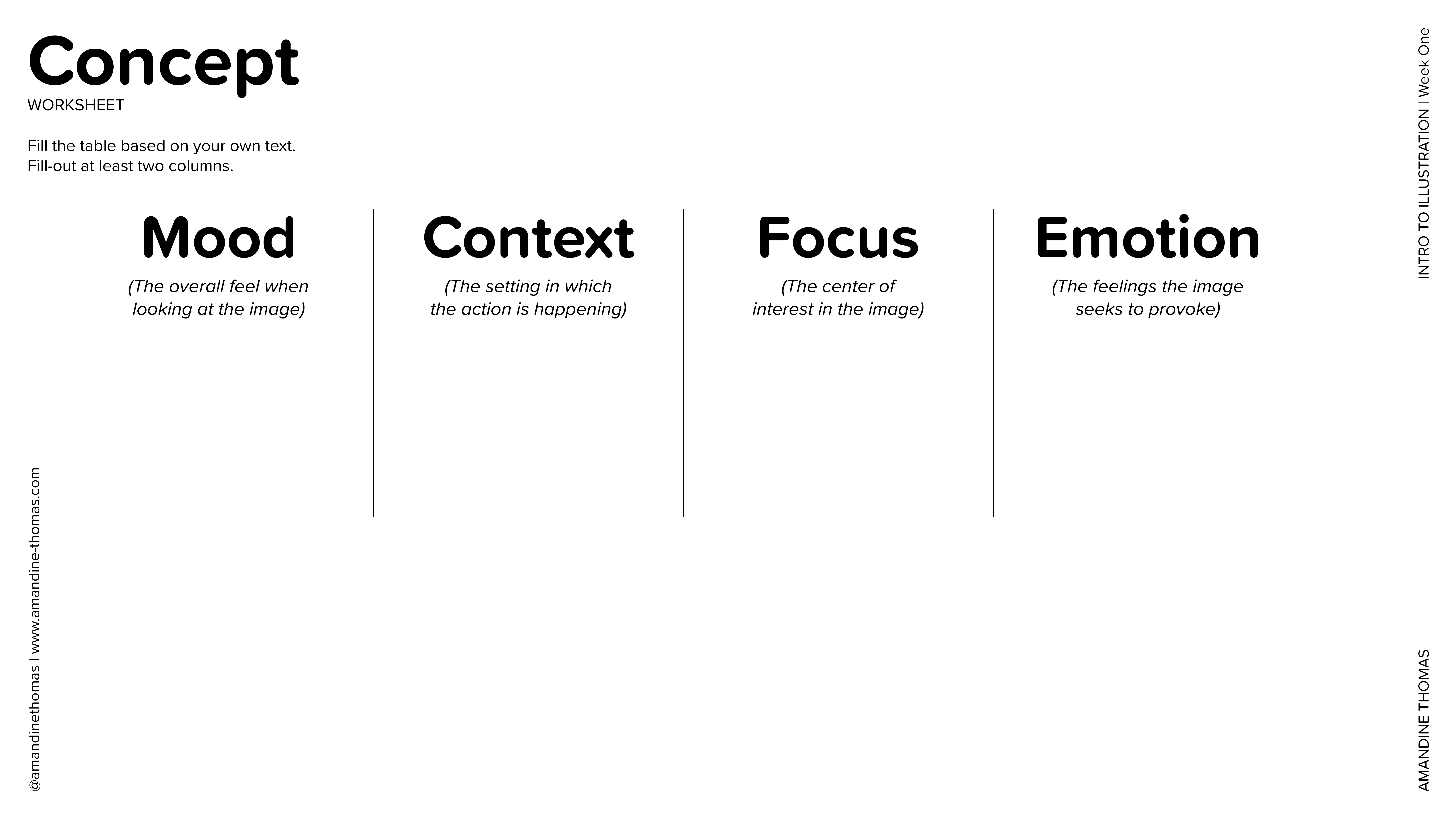

Looking back at the sentences you jotted down earlier, could you identify the mood? The context? The focus? The emotion? Using the worksheet below, try to fill-out at least two columns:

Then, based on your findings, complete the template below:

Set in a [mood], the illustration will take place in [context] and feature [focus]. It will seek to evoke a feeling of [emotion] for the reader.

Using my previous example, my concept now reads:

Set in a dream-like, fantastical atmosphere, the illustration will take place in a confusing, nonsensical garden and feature Alice talking to the flowers. It will seek to evoke a feeling of awe and bewilderment for the reader.

And now, you can start working on your illustration, equipped with a strong concept that will guide your creative choices throughout the entire process, from choosing a colour scheme to planning your layout!